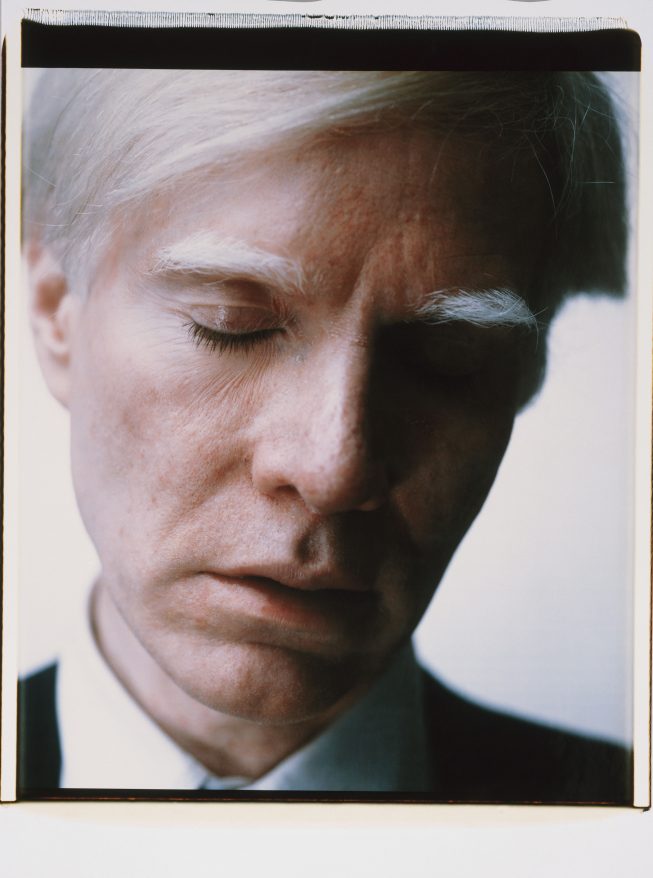

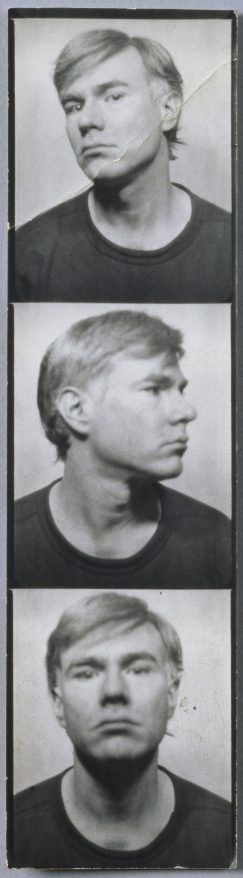

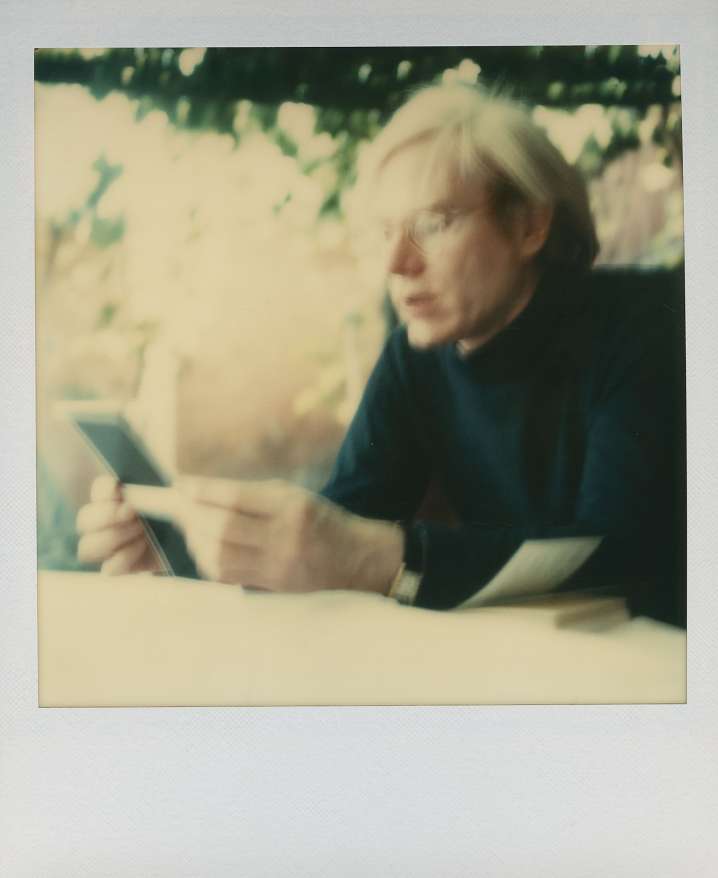

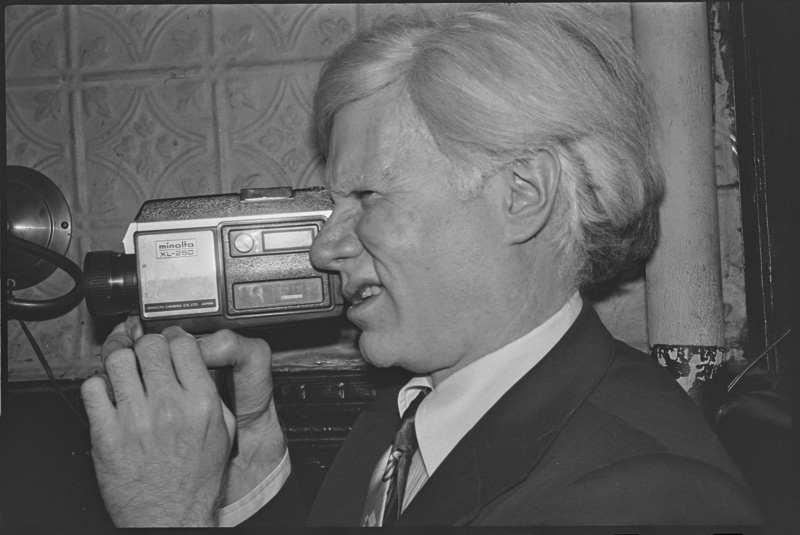

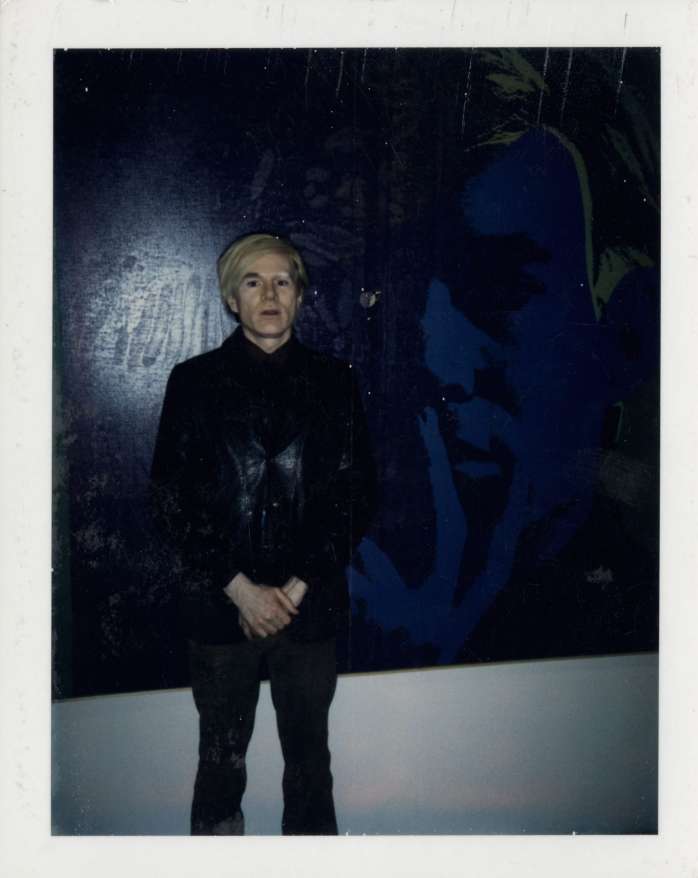

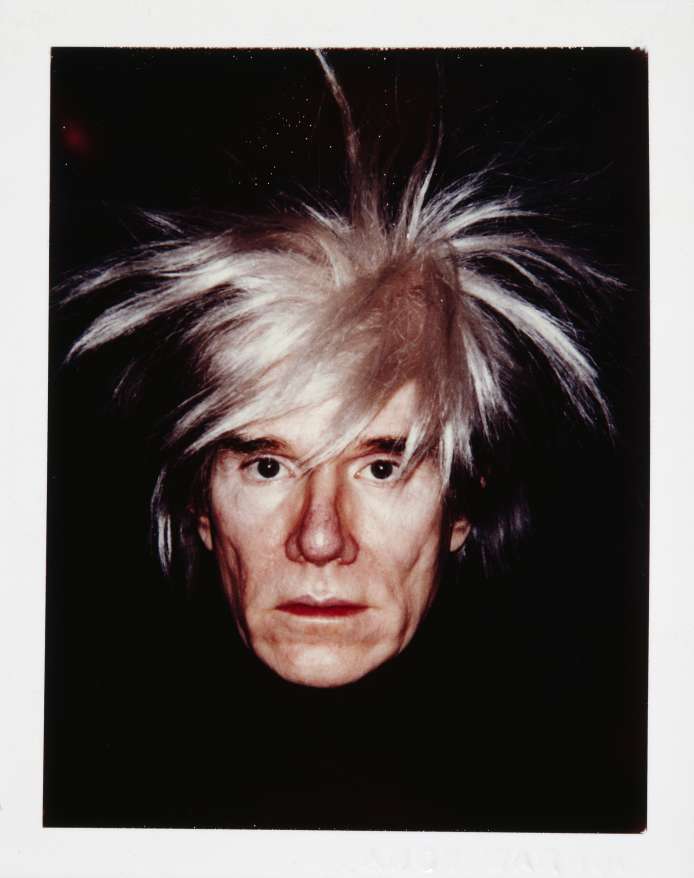

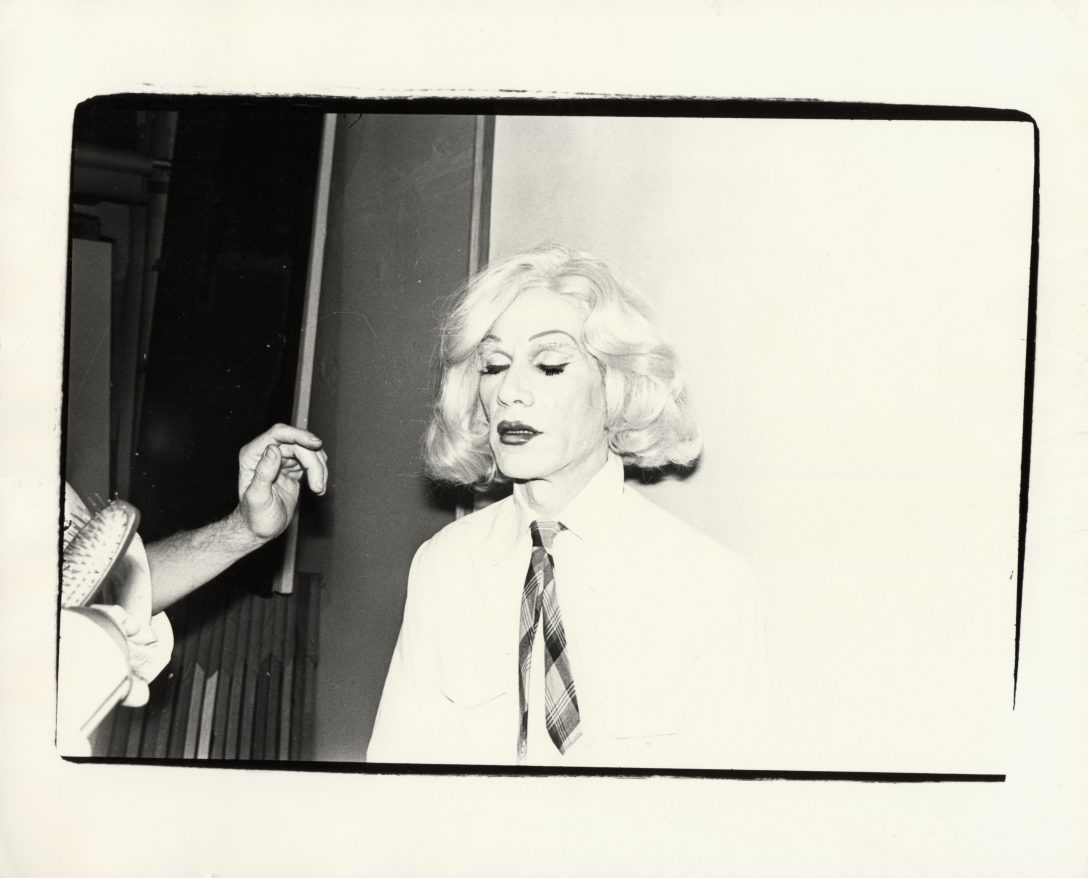

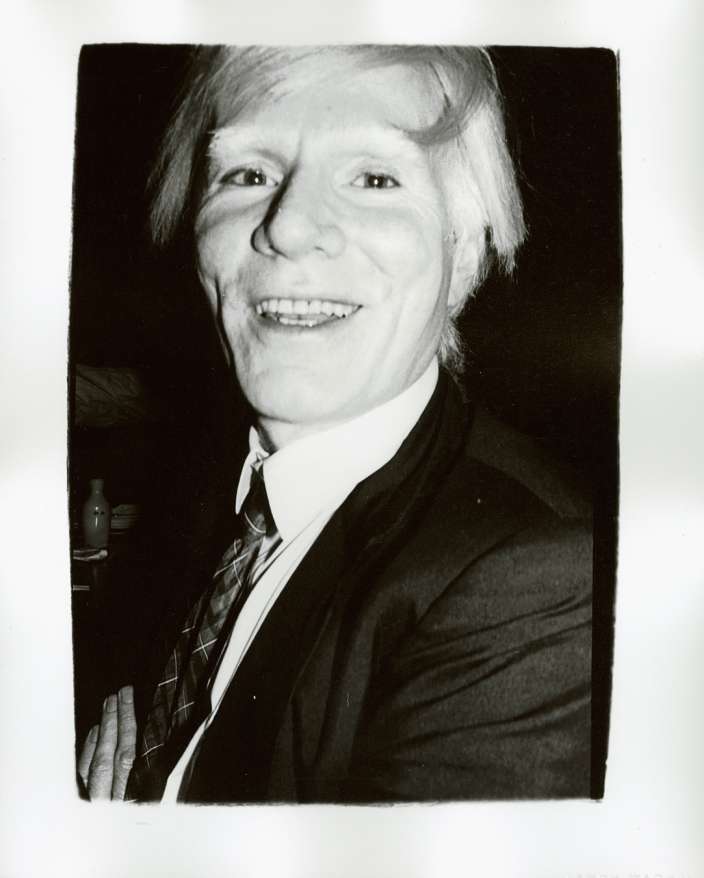

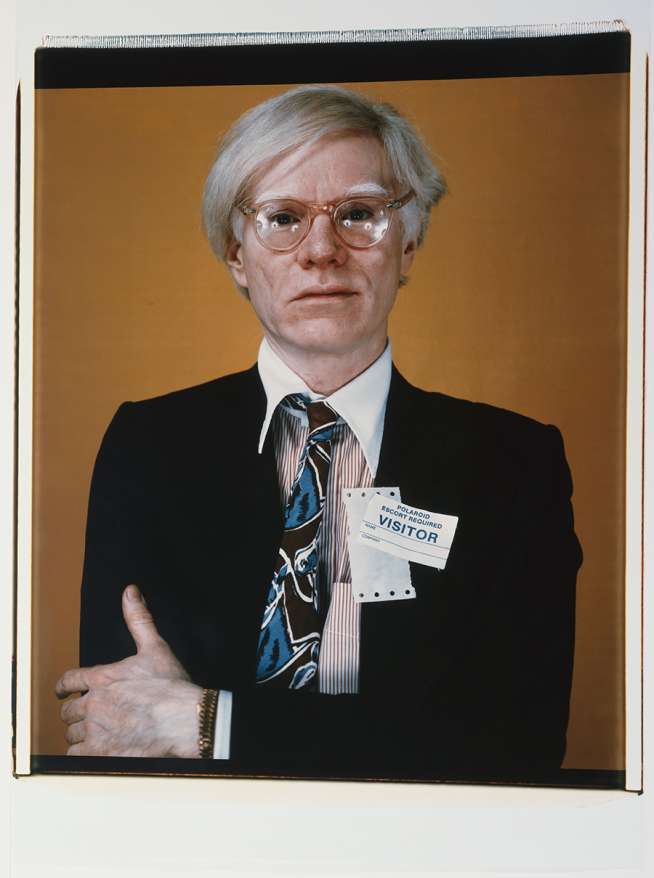

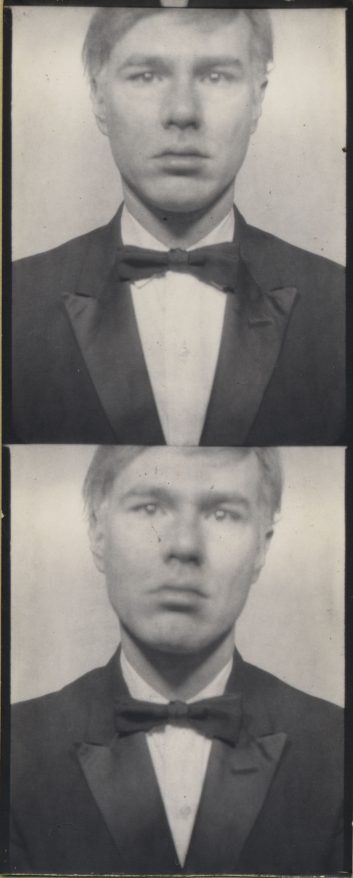

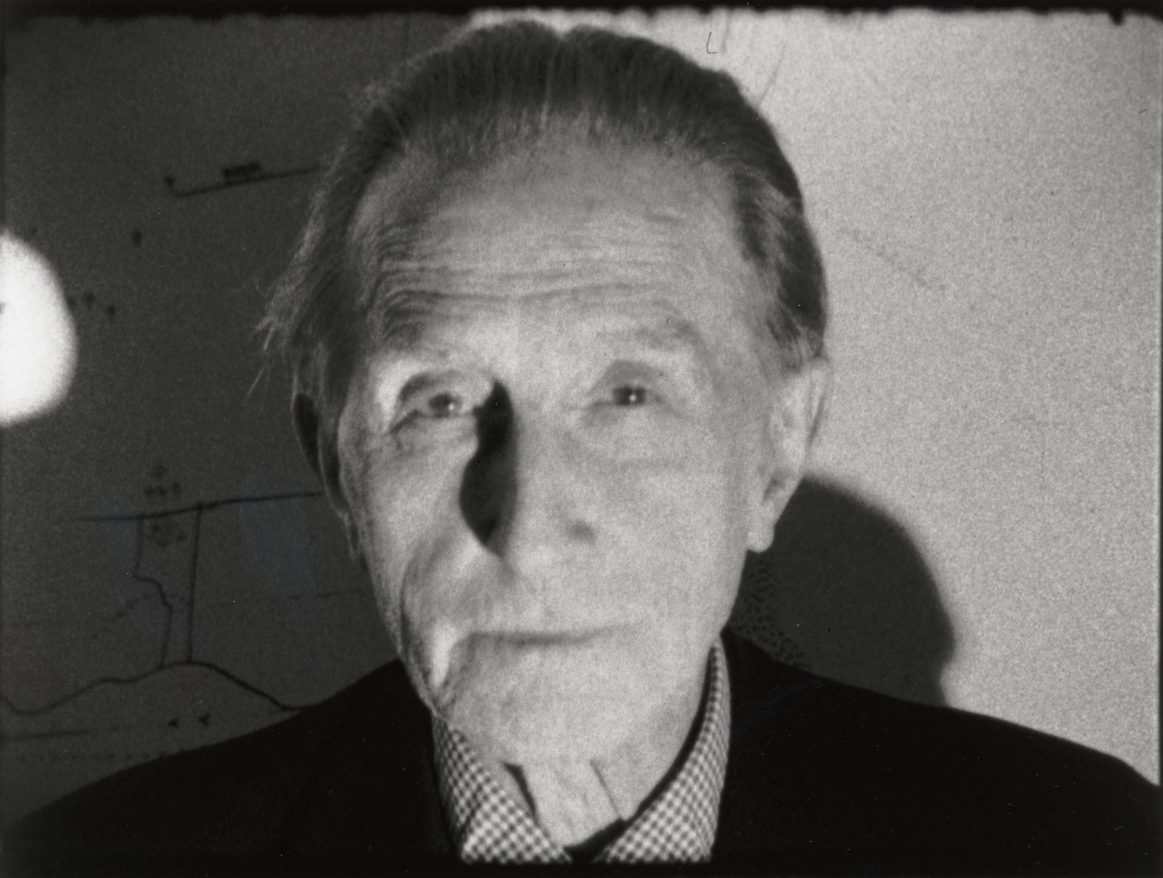

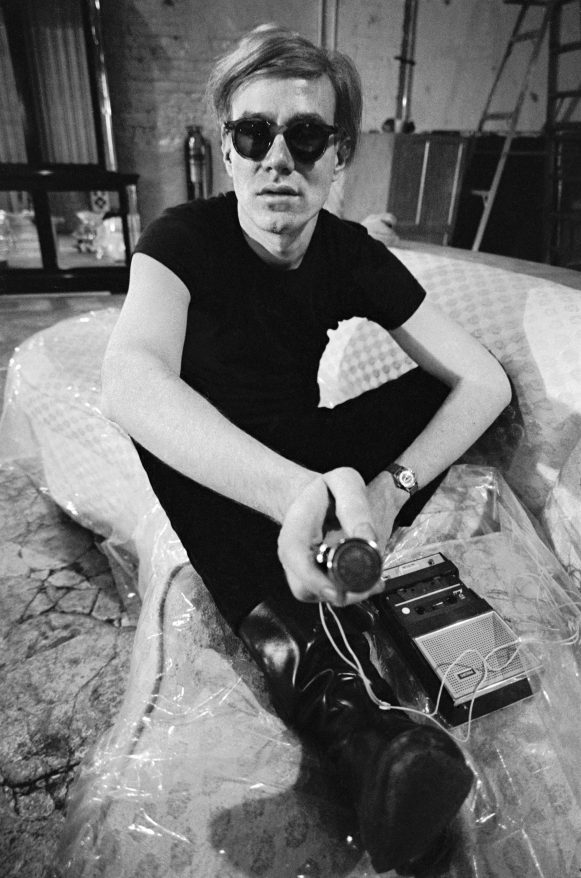

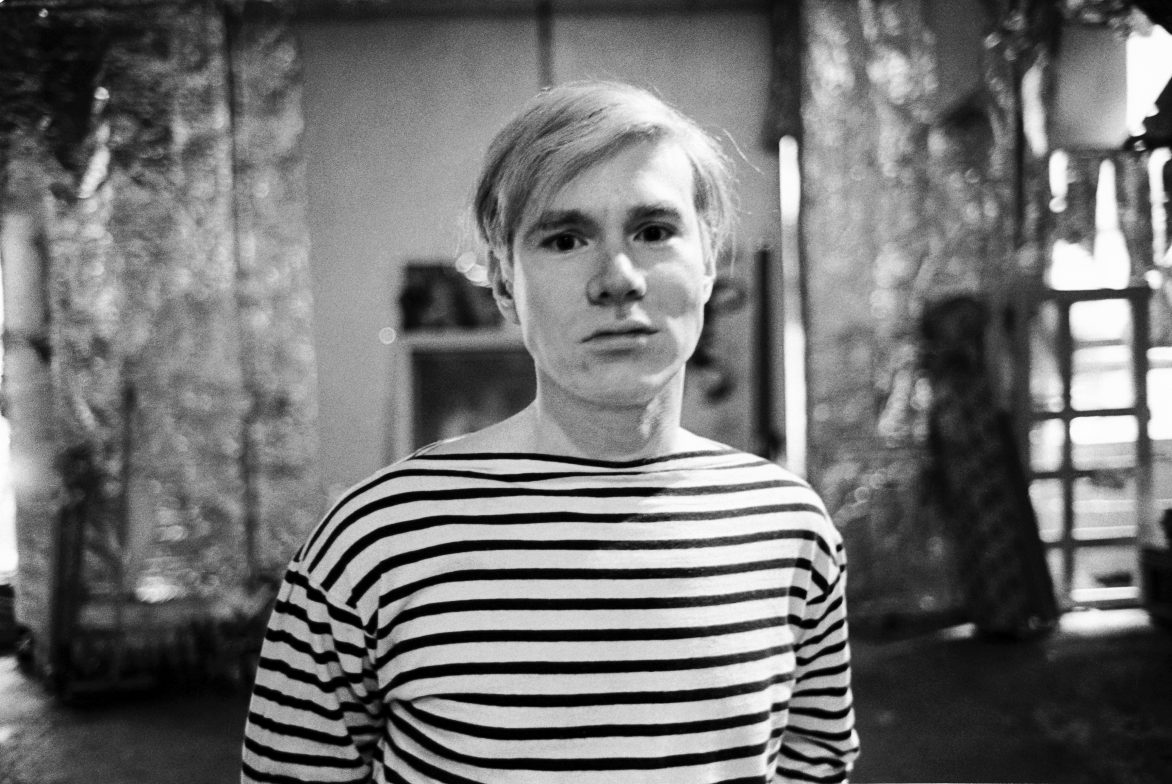

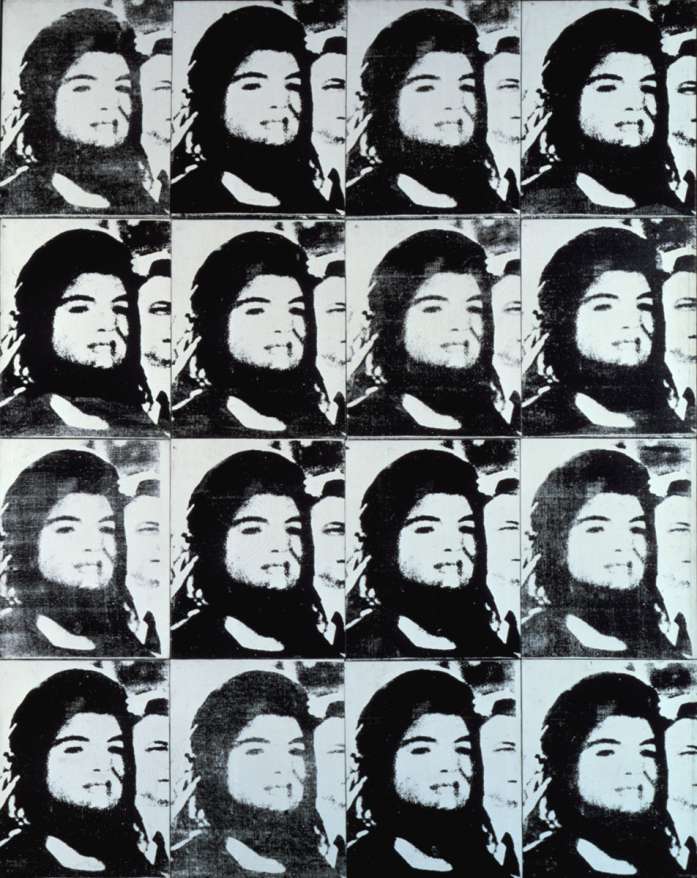

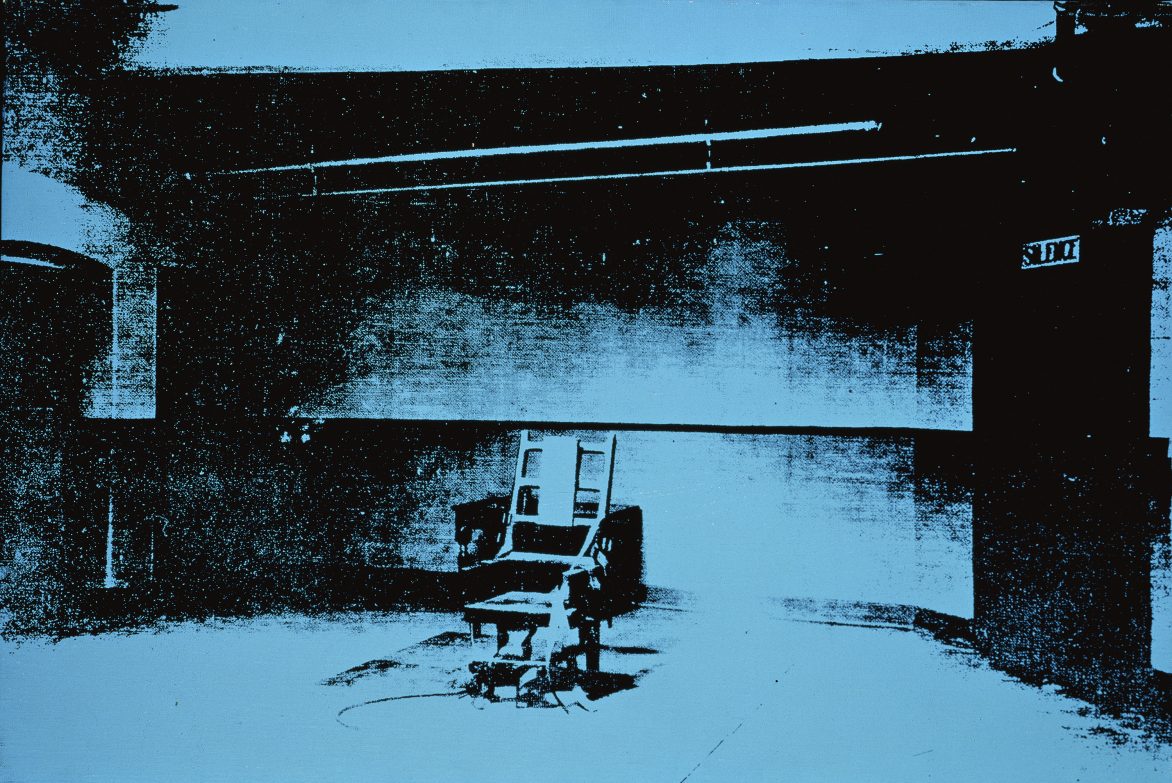

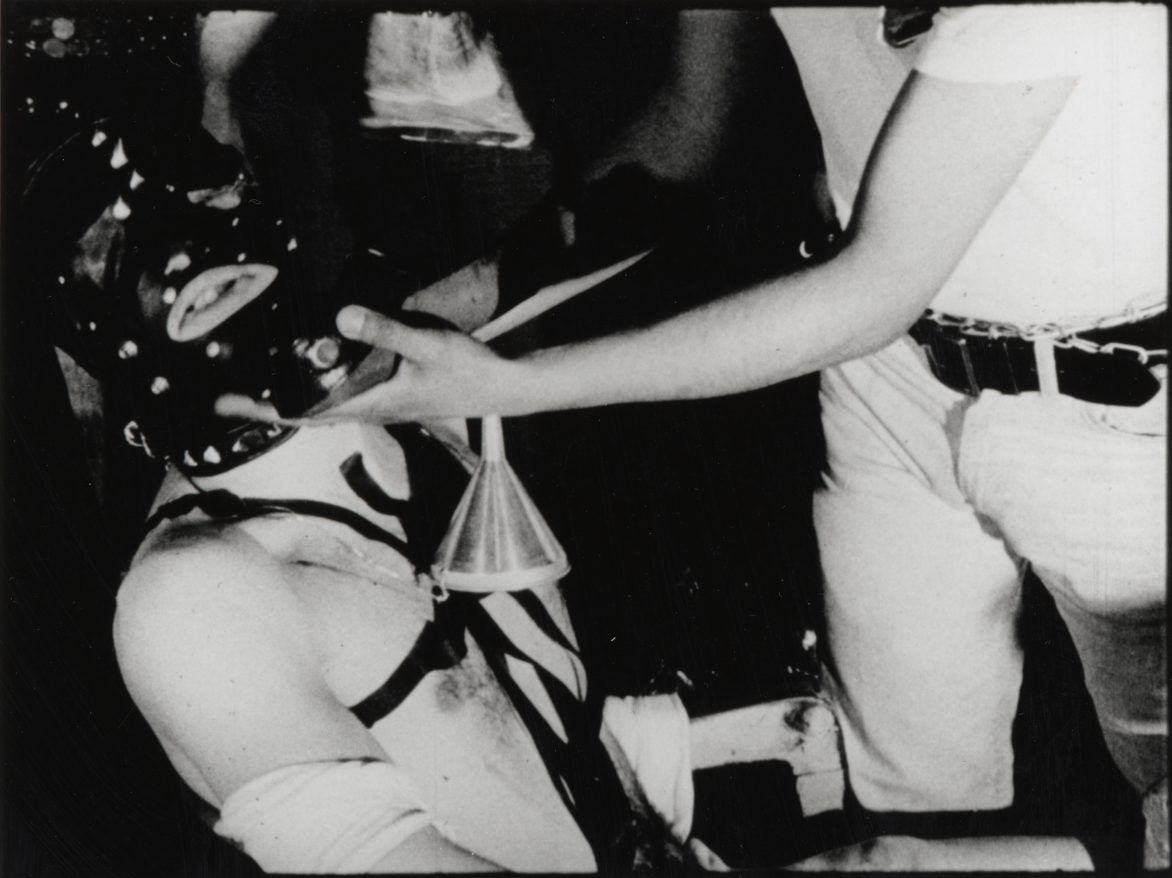

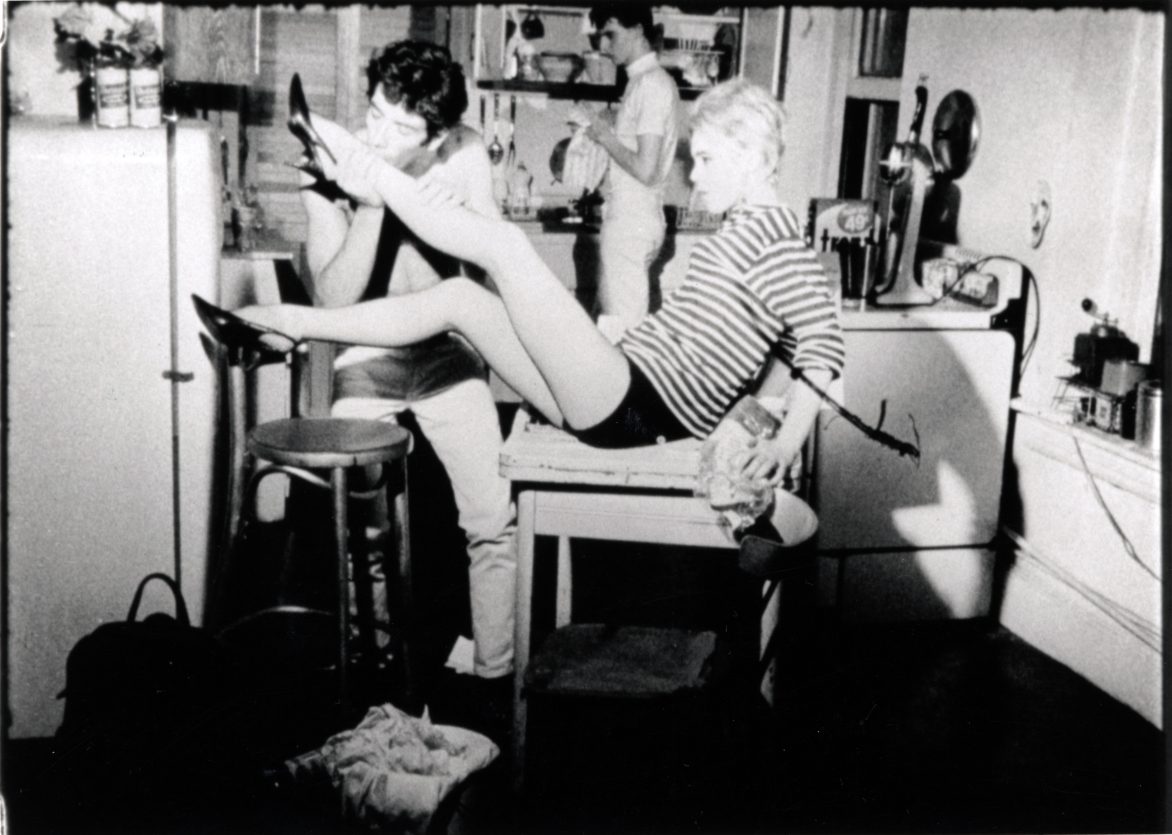

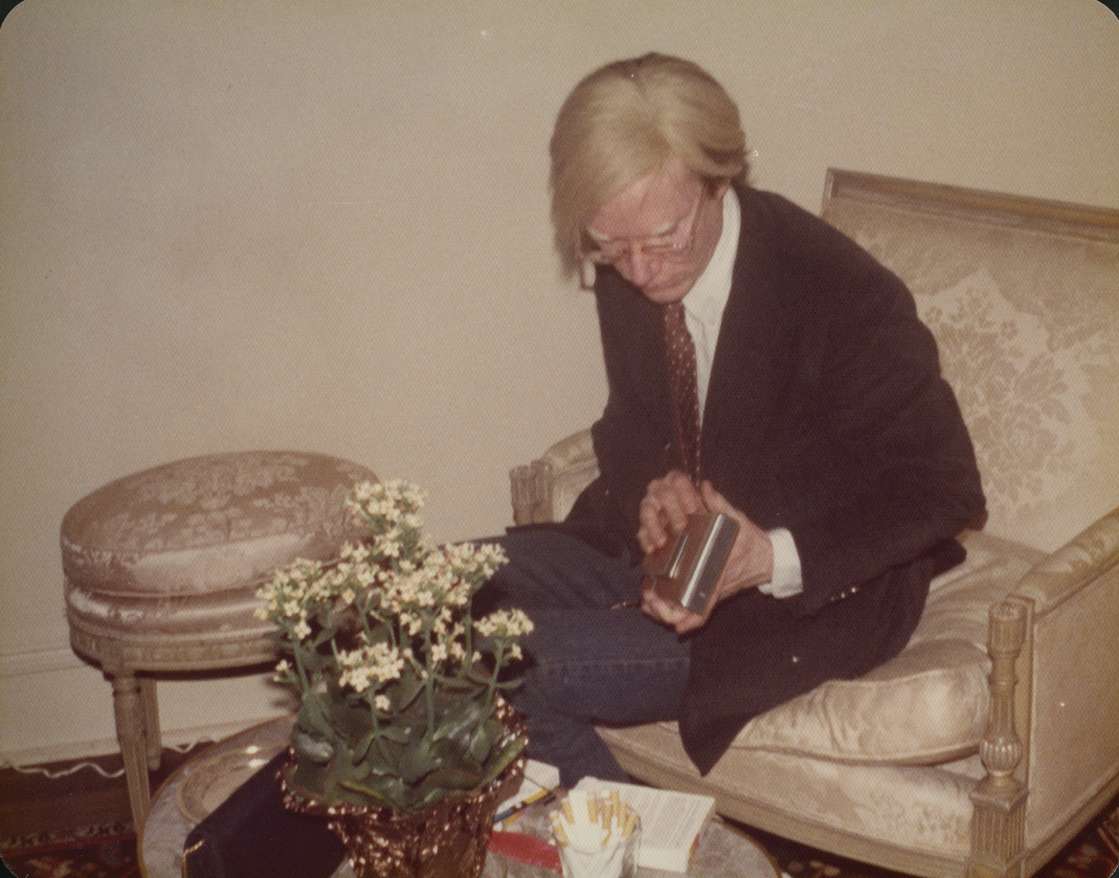

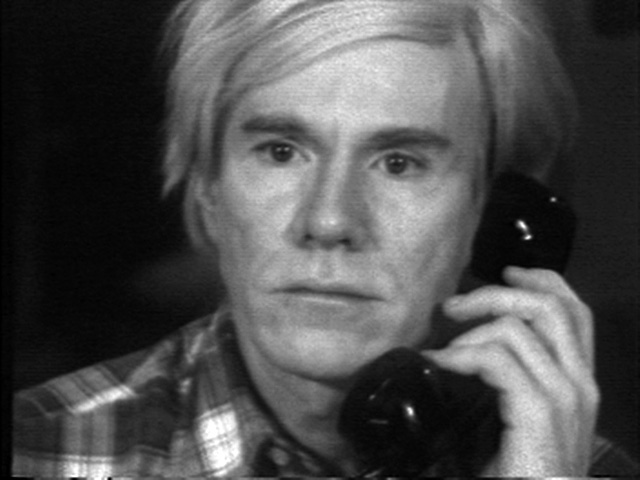

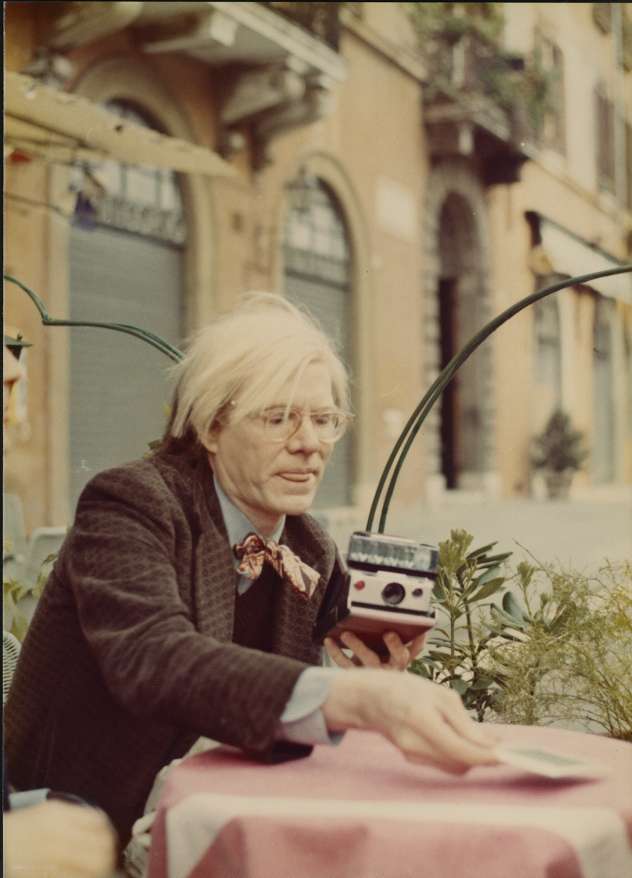

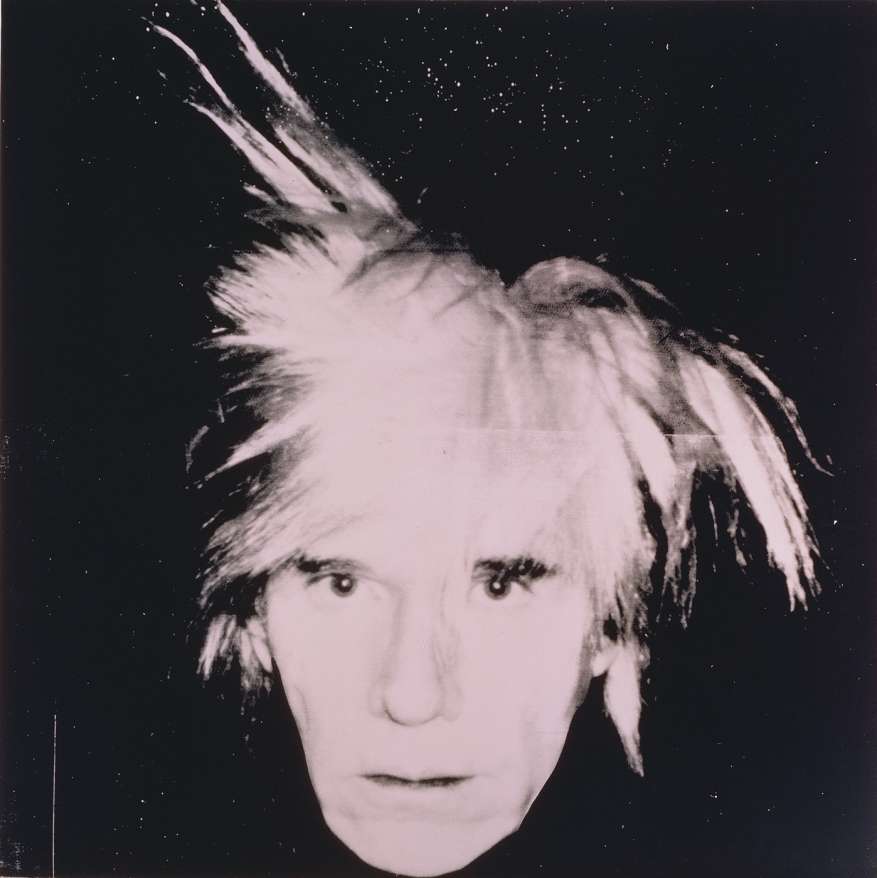

Andy Warhol changed the way we look at the world, and the way the world looks at art. With his exhaustive observation of cultural trends, from his rise to Pop art fame in the early 1960s up until his death in 1987, he identified the images and aesthetics shaping the consumer-driven postwar American experience, and transformed what he saw into a sophisticated yet accessible body of work. He invented new ways of image making, vastly expanding what was considered fine art, and also a new kind of artist, one who merged art and life, and treated painting, photography, filmmaking, writing, publishing, advertising, branding, performance, video, television, digital media—and even his own persona—as equally valid terrain for creative experimentation. Often lost in his own celebrity and myth is the fact that he is widely considered one of the most important postwar artists of the 20th century.

Biography

“Isn’t life a series of images that change as they repeat themselves?”

Andy Warhol

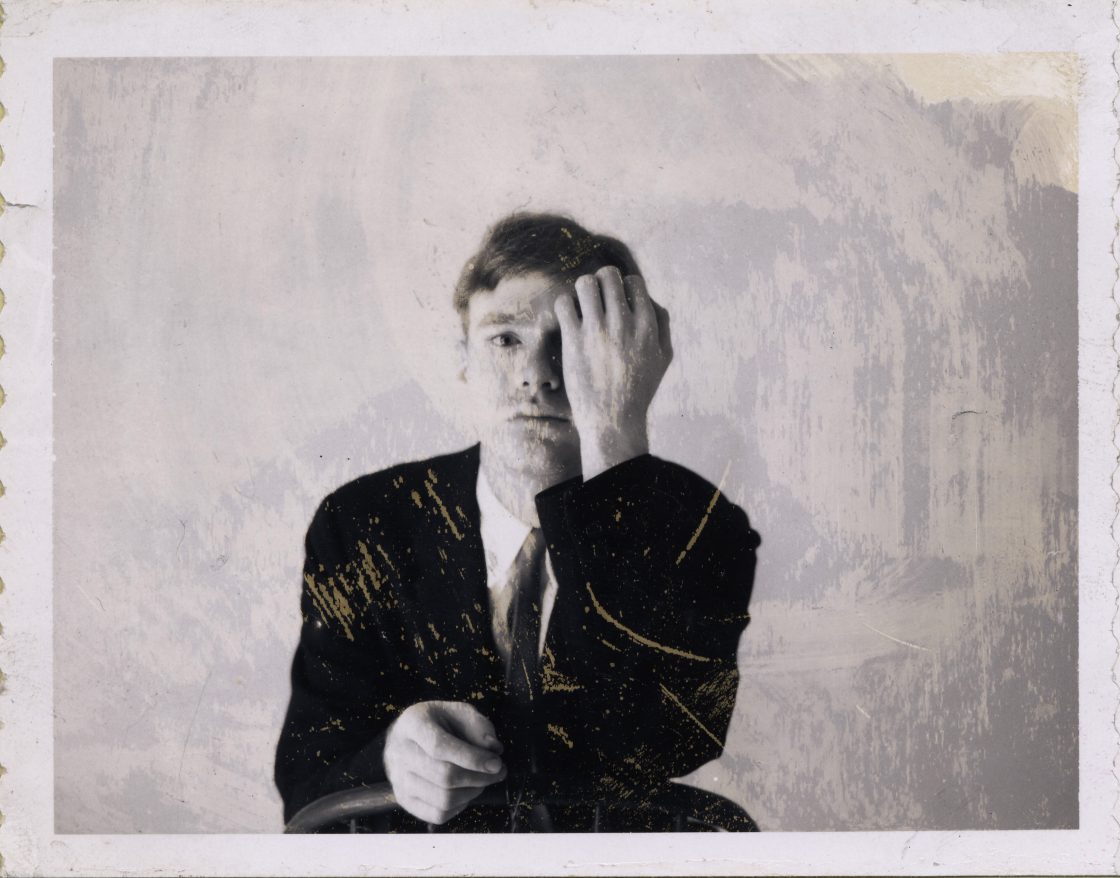

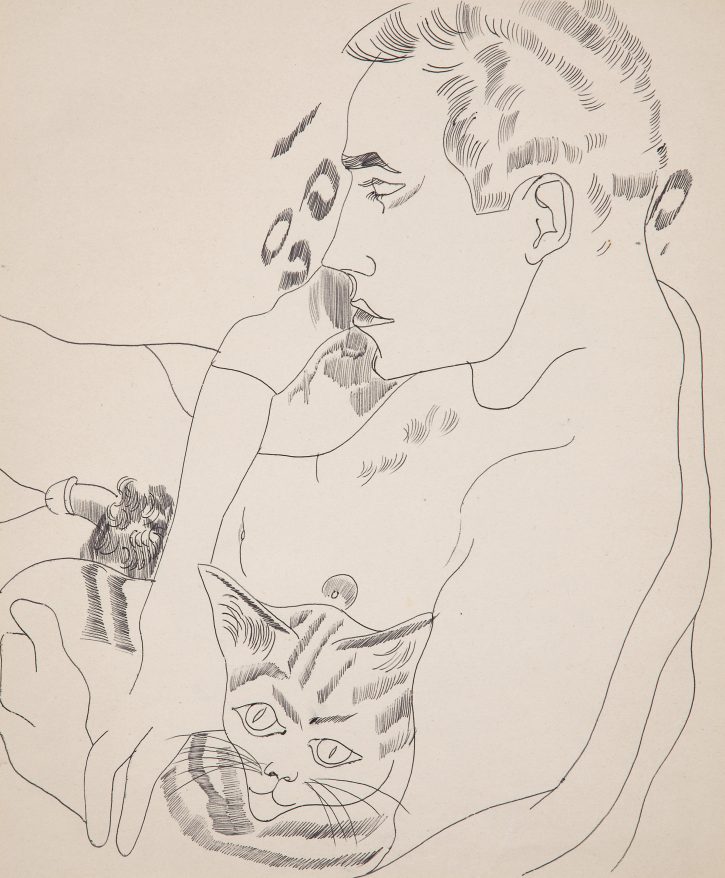

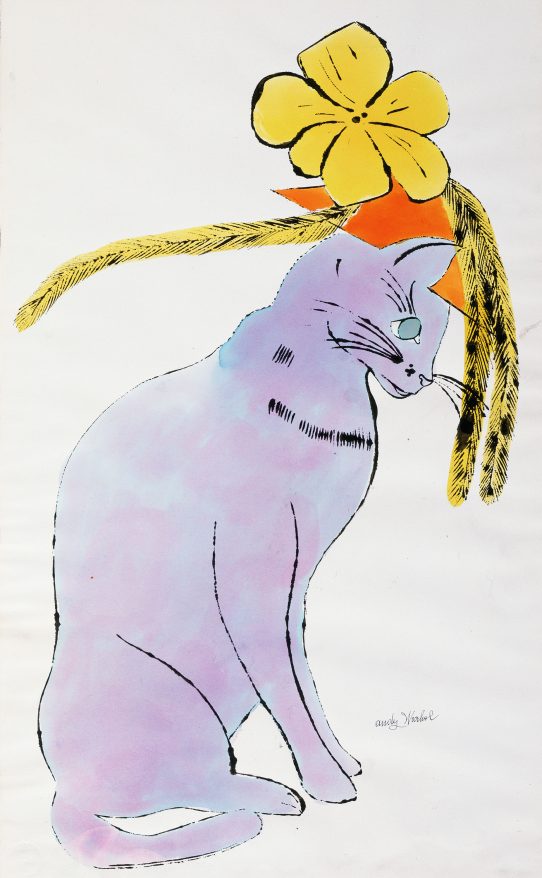

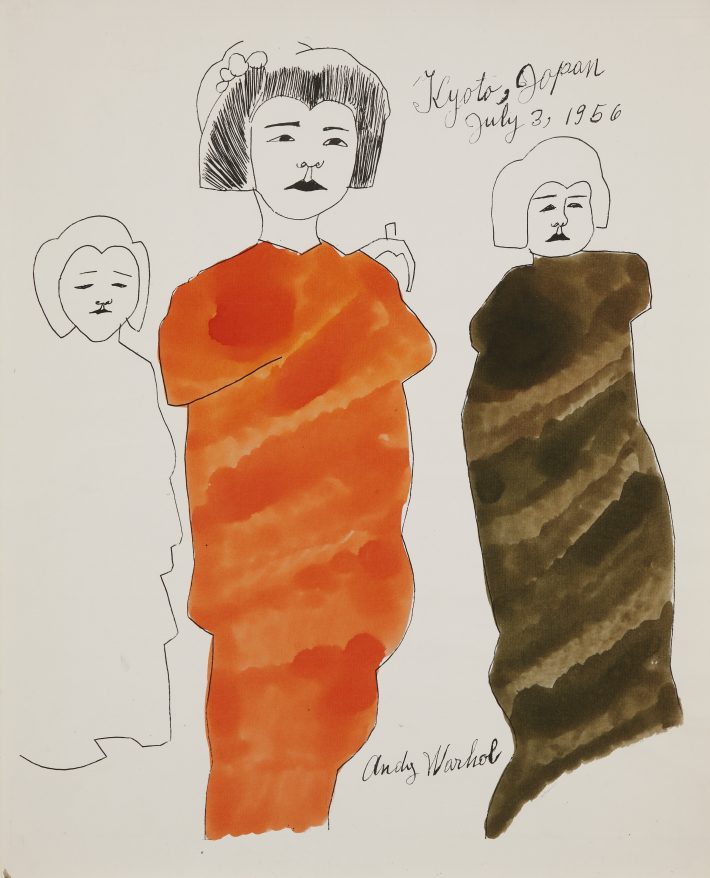

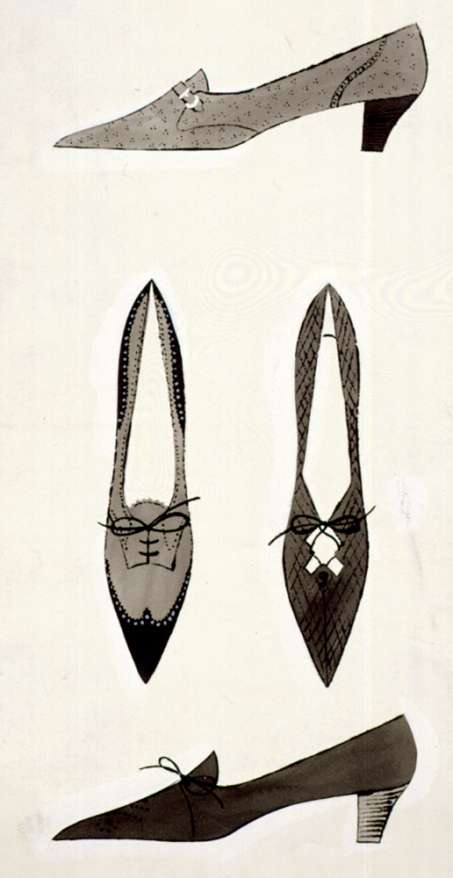

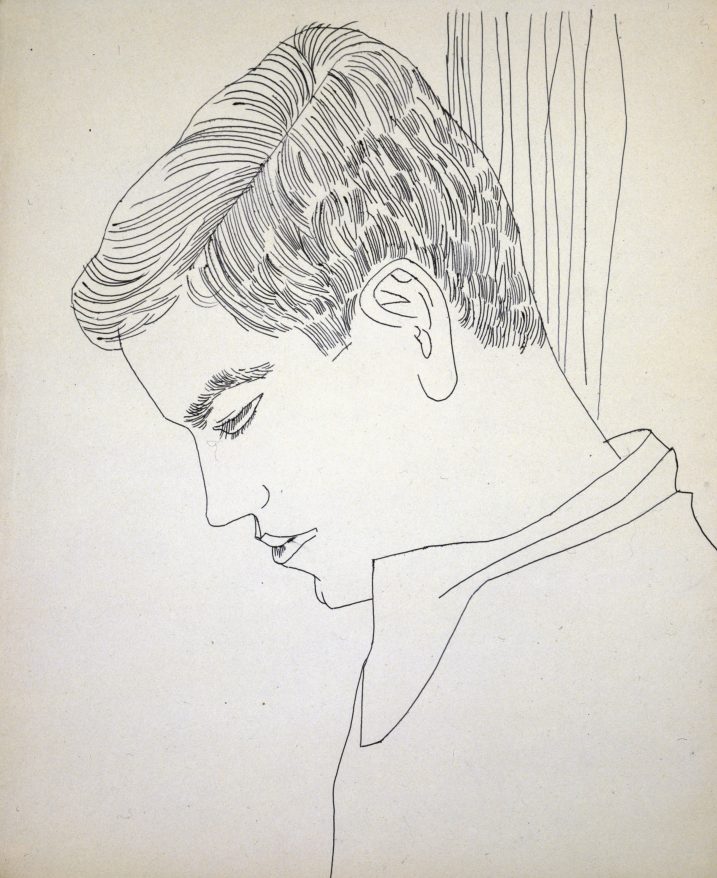

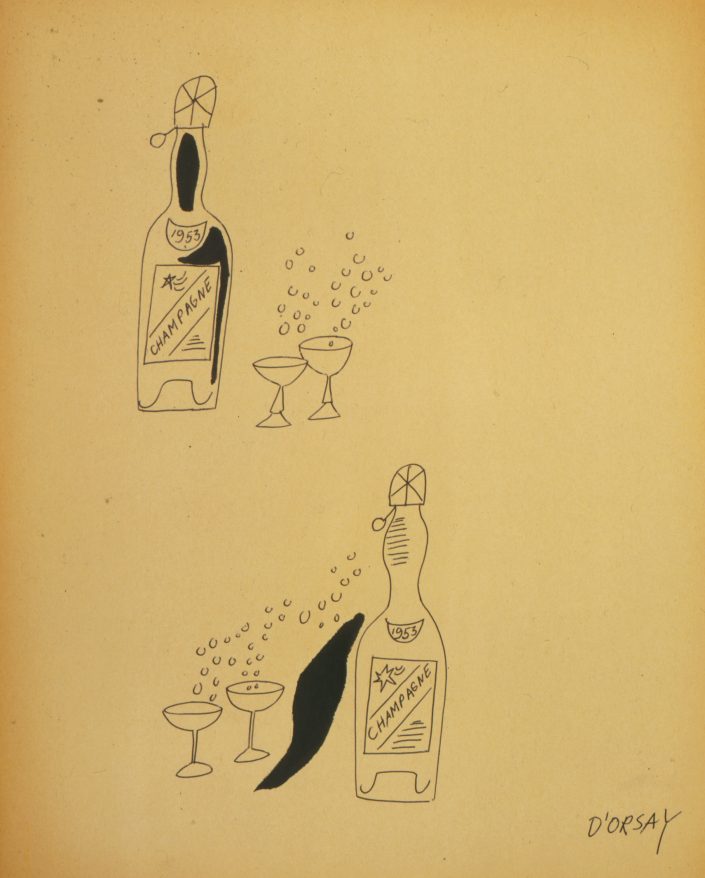

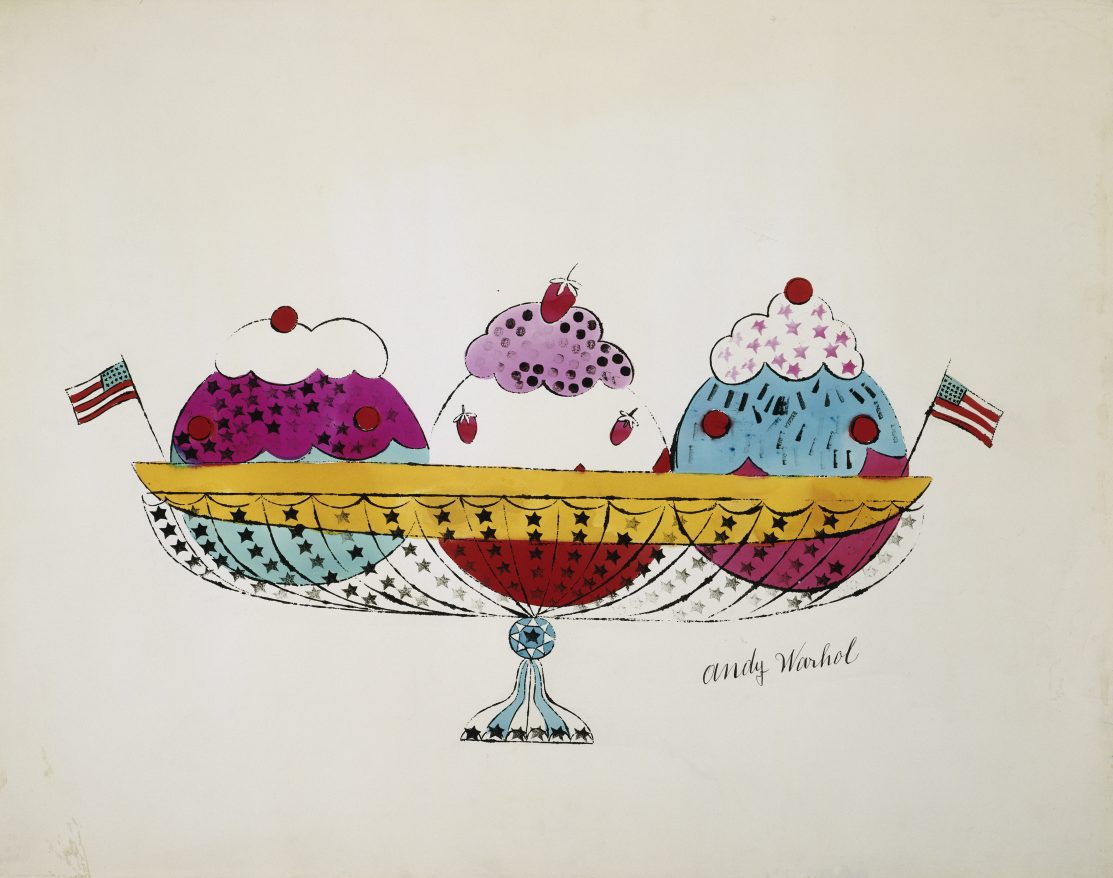

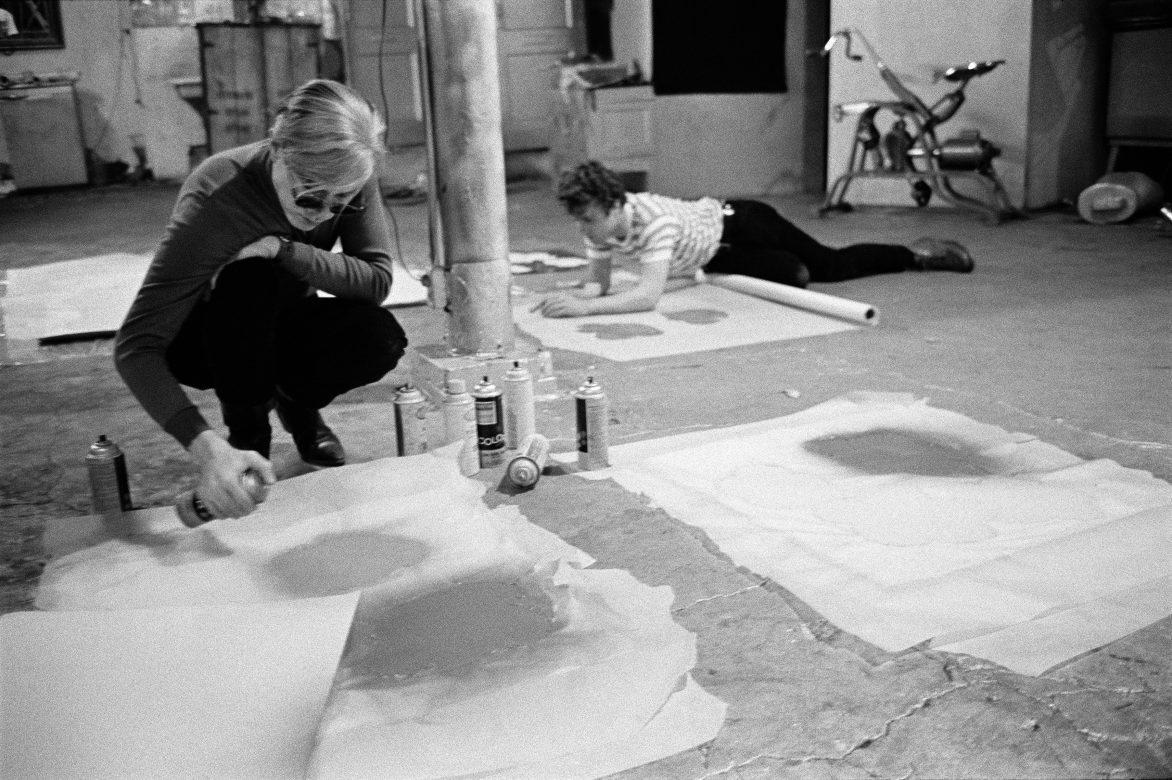

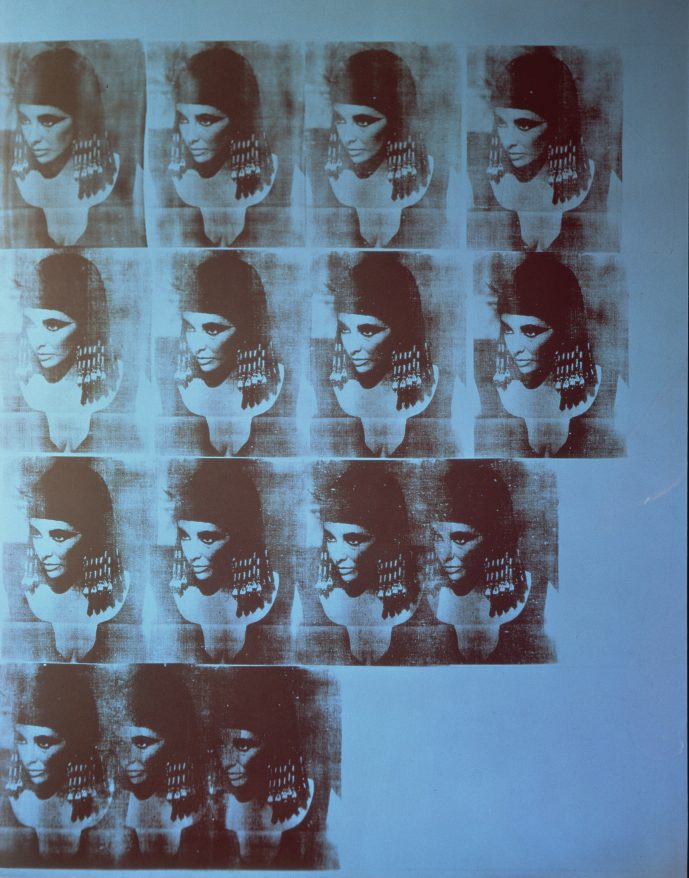

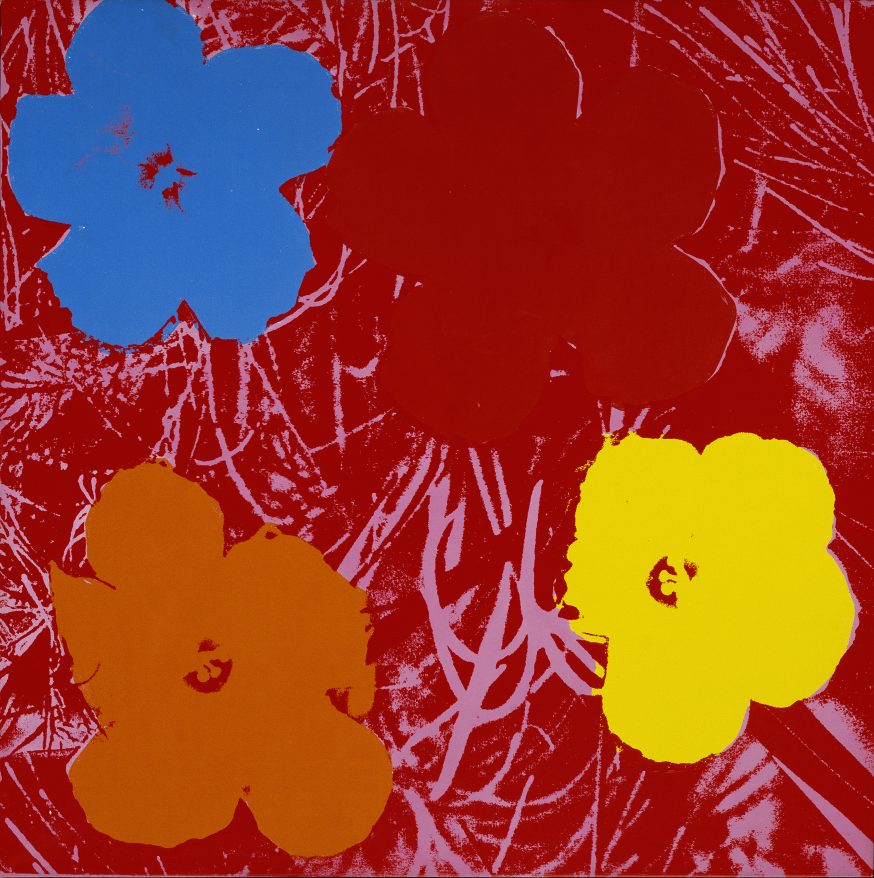

Warhol’s fashionable sought-after style looked different than other illustrations, characterized by his jagged “blotted line,” which he achieved by pressing paper to a wet ink drawing to create a blotchier duplicate. As curator Donna De Salvo has pointed out, the duplicate looked simultaneously handmade and mass-produced – an appealing duality long at the core of Warhol’s aesthetic. That simple form of printing foreshadowed the radical experiments with silkscreening that he’d use to forever transform the look and feel of painting.

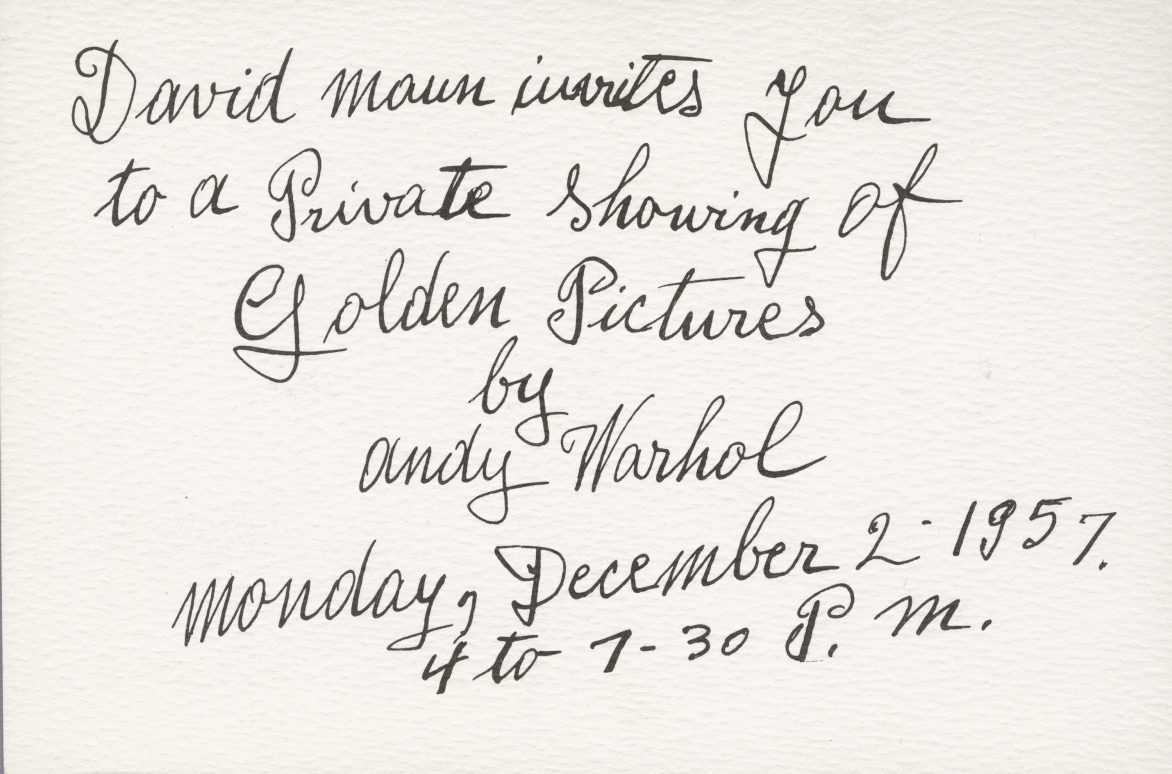

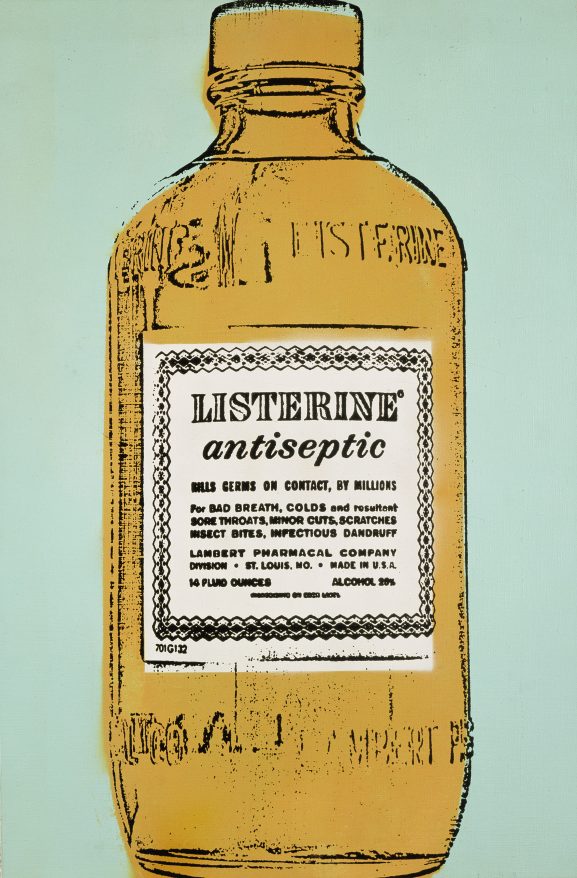

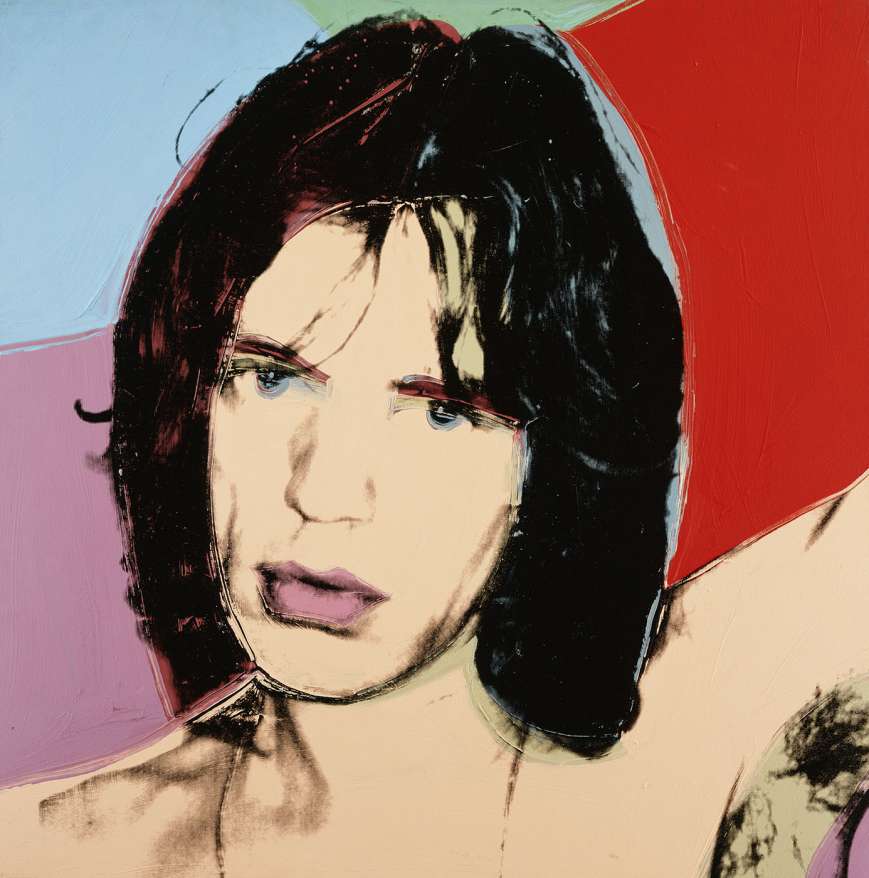

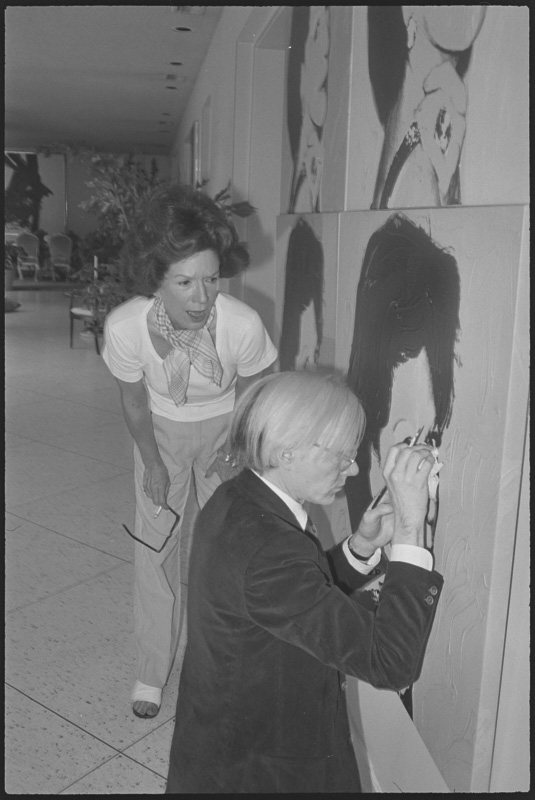

By the late 1950s, Warhol had earned enough as an illustrator to purchase a townhouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, and to fill it with American antiques and folk art. He also began collecting work by his contemporaries, including Jasper Johns, Ray Johnson, and Frank Stella, whose vanguard ranks he aspired to join. Although a regular visitor to the city’s progressive galleries, where Pop Art was beginning to percolate, Warhol was also somewhat of an art world outsider—“too swish,” as he later described, for the more discreetly gay social circle of Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg. Neither his homoerotic drawings nor his comic-book inspired images caught on, and Warhol faced a number of rejections from dealers. But his Campbell Soup Cans were a different story. When dealer Irving Blum of the cutting-edge Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles spotted the paintings during a studio visit, he offered Warhol a solo exhibition on the spot. He created 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans for the 1962 show, each a different variety, hand-painted to mimic the uniformity of mass production. He described the canvases as “portraits”—a genre he’d continue to explore in depth for the next 35 years.

“Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art”

Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again)

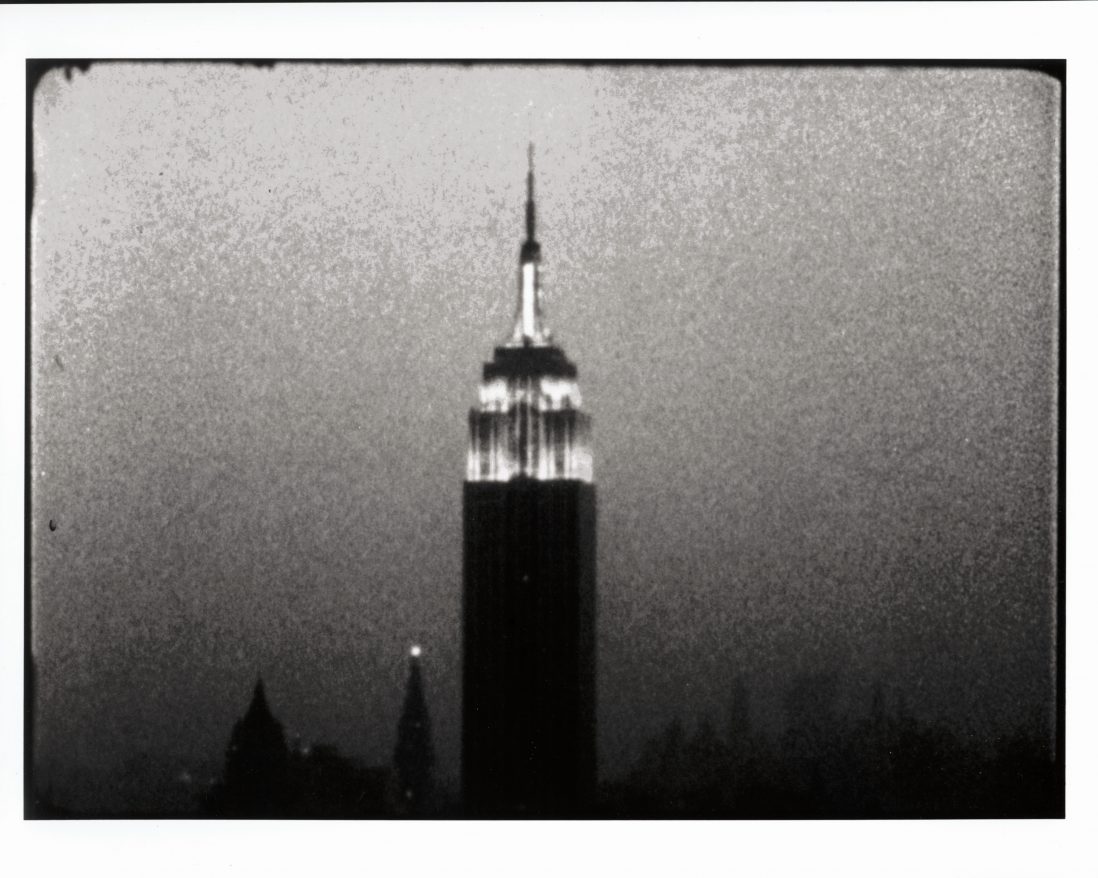

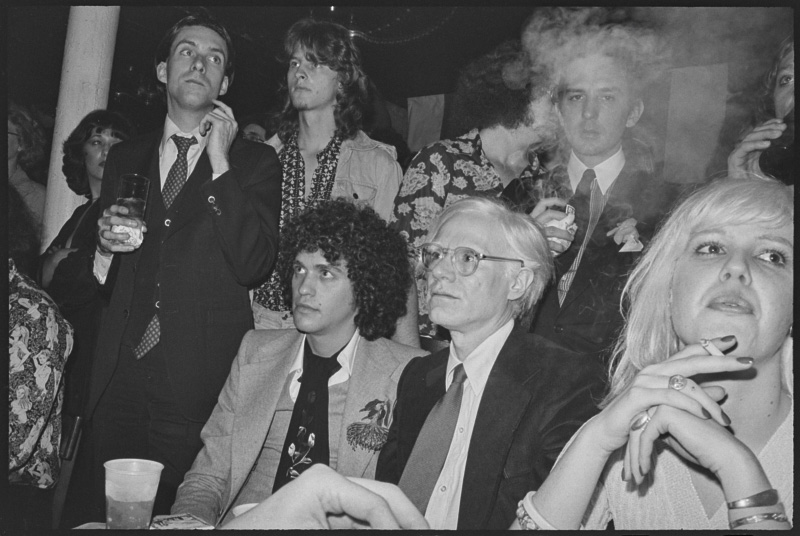

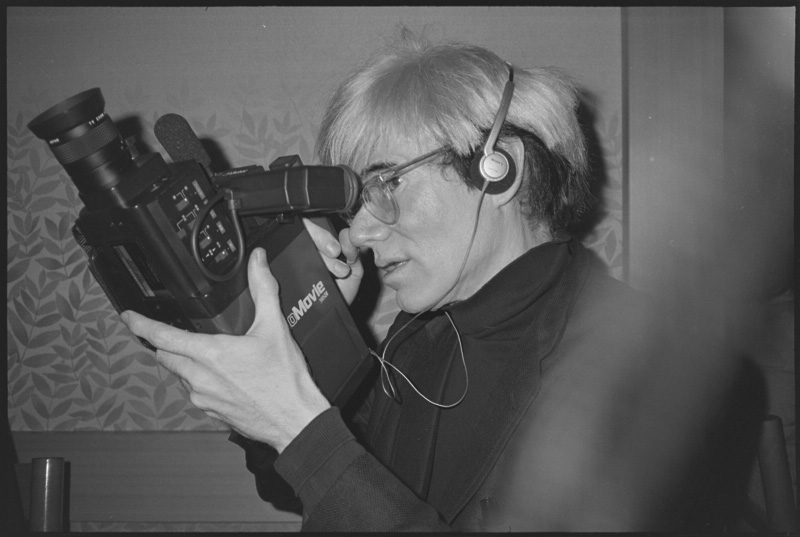

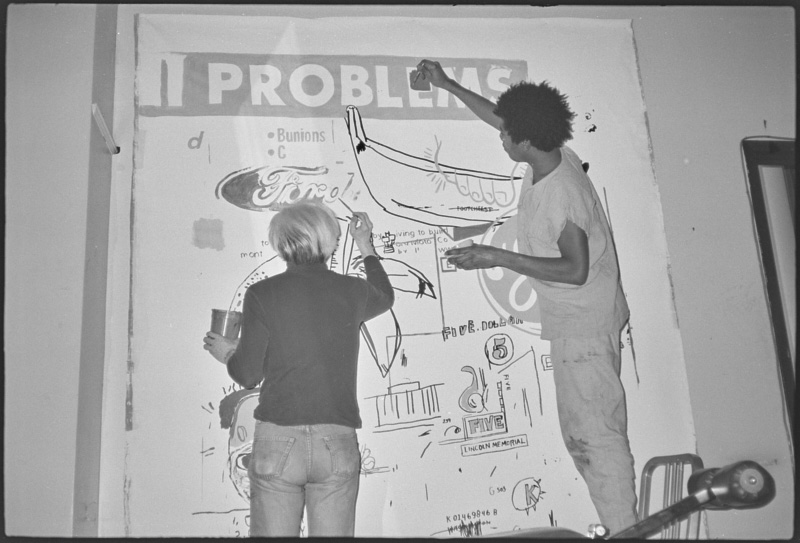

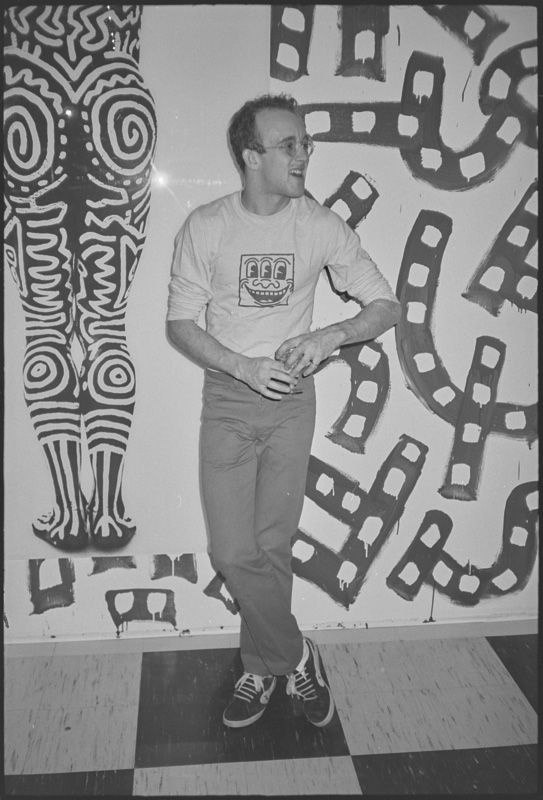

Warhol continued expanding his artistic vision, as changing tastes and technology reshaped culture in the 1980s. He made music videos, created computer art, and produced experimental television shows that merged the fashion, entertainment, and art world (including Andy Warhol’s Fifteen Minutes, which aired on MTV). Open to the vibrant new forms emerging from the East Village art scene in the 1980s, Warhol teamed up with young painter Jean Michel-Basquiat (who would become a close friend) to collaborate on a series that combined his readymade iconography of logos with the rising star’s graffiti-style expressionism.

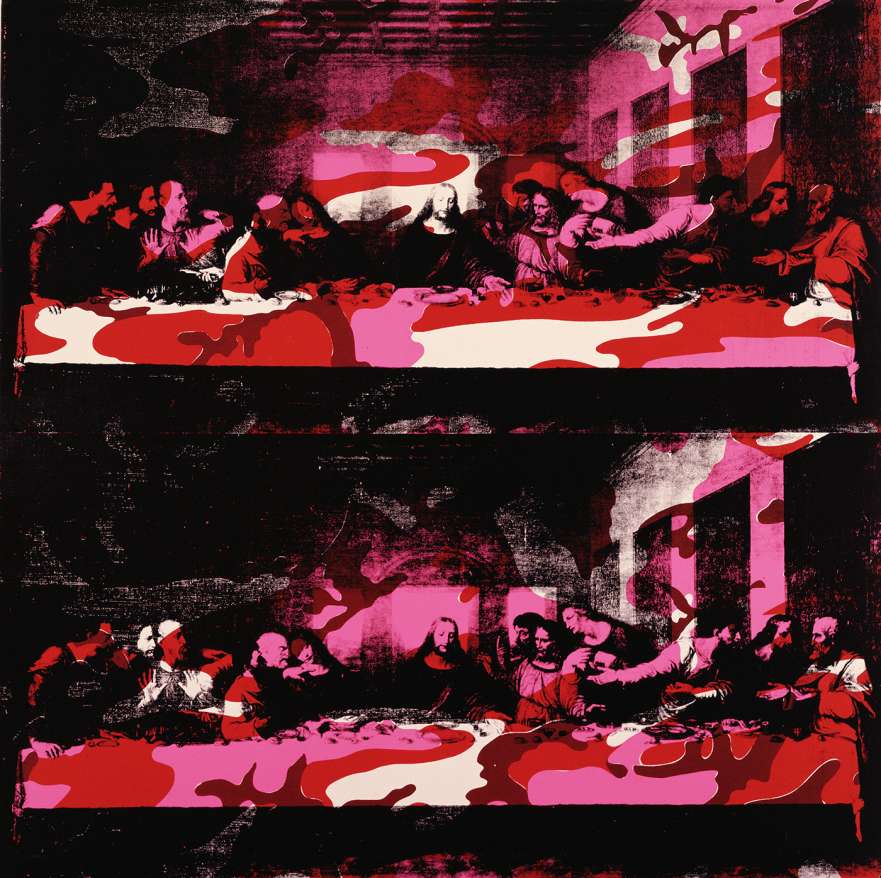

The year before his death, Warhol’s independent studio practice remained as prolific and zeitgeist-tapping as ever. In 1986, he painted more than 100 works related to Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, which some have read as complex reckoning of his homosexuality, Catholicism, and mortality in response to witnessing AIDS devastate the gay community

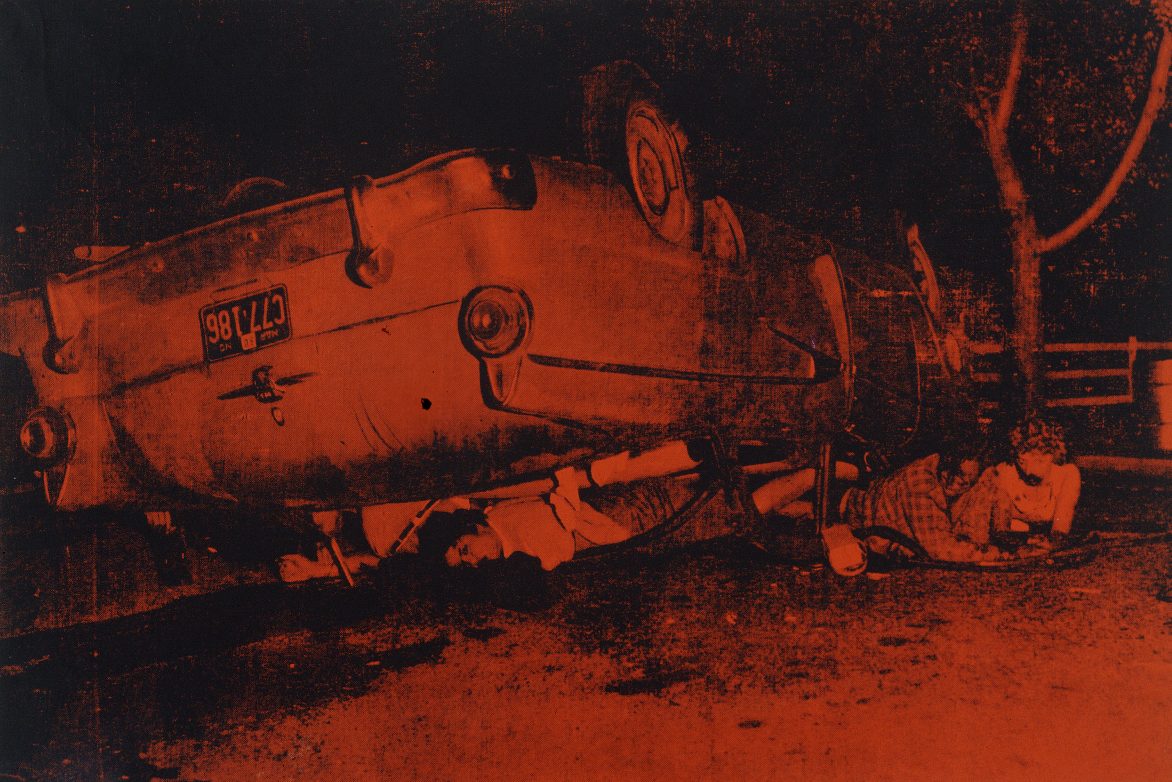

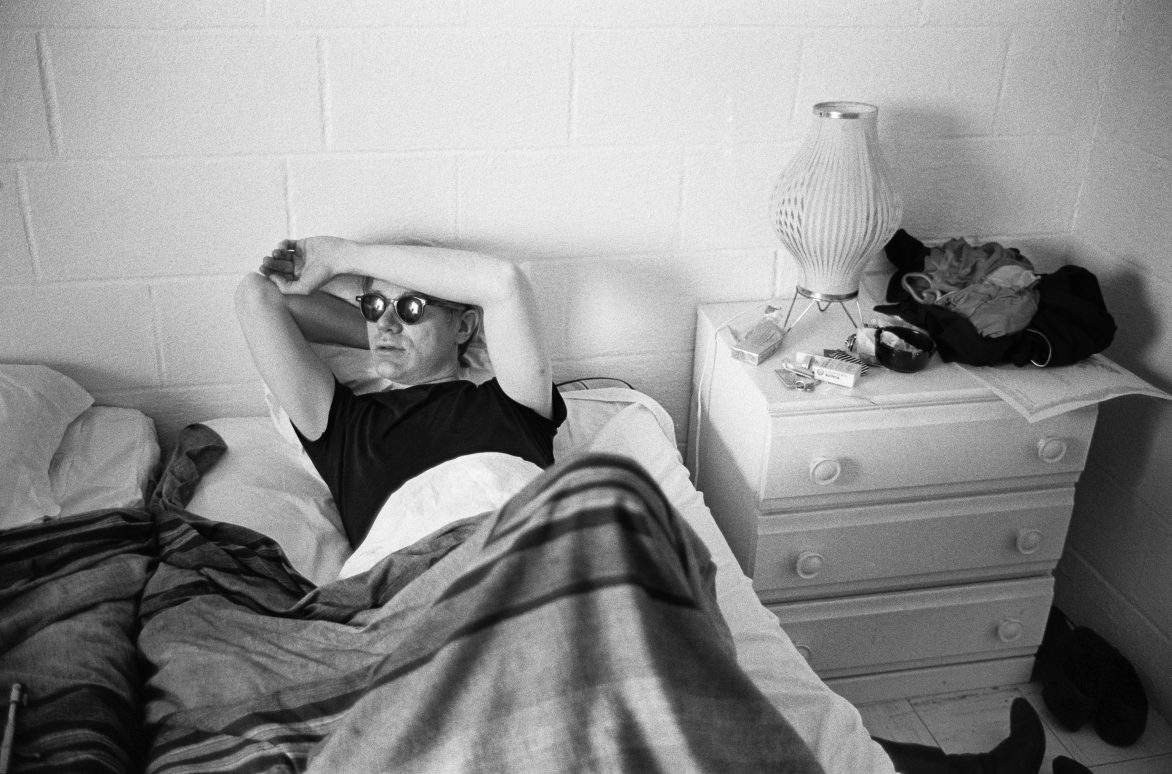

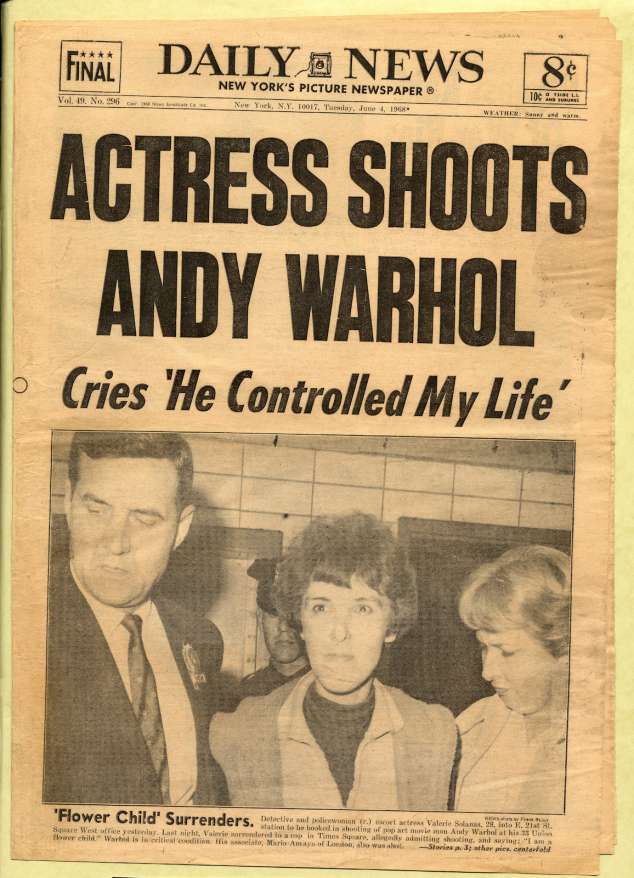

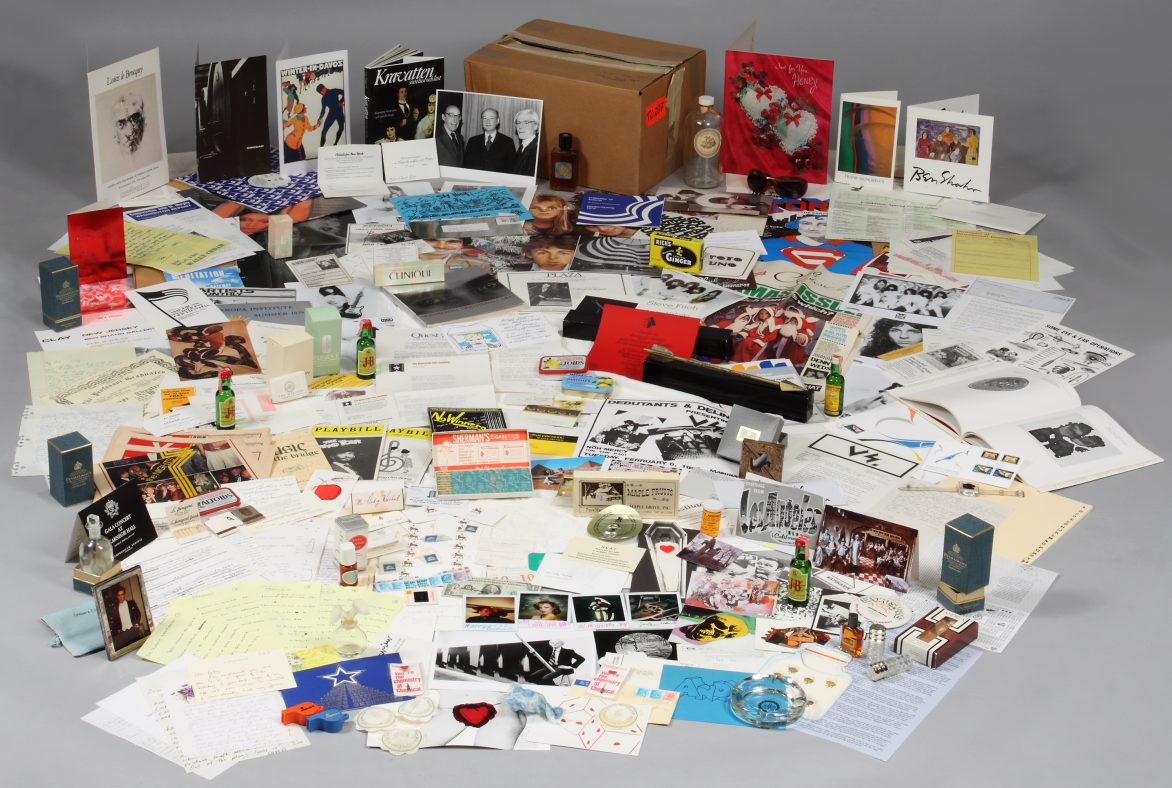

Warhol died unexpectedly in February 1987 from complications following routine gallbladder surgery. He was just 58. Thousands attended his mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. Death had long fascinated Warhol — even before his own near-death experience in 1968. We see it in his Marilyns and 13 Most Wanted, in his Skulls and Last Suppers. In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, he mused: “I don’t believe in it, because you’re not around to know that it’s happened. I can’t say anything about it because I’m not prepared for it.” But in a way, Warhol had prepared for it. In his will he called for the creation of a foundation dedicated to “the advancement of the visual arts.” In doing so, he ensured that future generations would keep pushing art in radical new directions — and that his death would be a starting point rather than an ending.

See Also

Founded in 2013 and launched in 2015 Common Field is a national network of independent visual arts organizations and organizers that connects, supports, and advocates for the artist-centered field.