The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, PA was cofounded in 1989 by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, the Dia Art Foundation, and Carnegie Institute. Home to more than 500,000 objects, it is the largest repository of Warhol’s artwork and archival materials and among the most comprehensive single-artist museums in the world. Since opening to the public in 1994 in a converted historical warehouse, the museum has facilitated a proliferation of rigorous Warhol-related scholarship, research, and curatorial innovation, vastly broadening our understanding of the profound artistic and cultural impact of one of the most complex, influential, and mythologized cultural figures of the 20th century.

While the Foundation played a pivotal role in establishing it, The Warhol museum is an independent institution within the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh organization. The Foundation initially donated more than 3,000 artworks and films, as well as archives, personal belongings, and other ephemera from the artist’s estate to form the museum’s core collection and also awarded a $2 million grant to help fund architect Richard Gluckman’s conversion of the 1911 industrial building into a state-of-the-art space. The museum now occupies eight floors where Warhol’s art, films, videos, and archives can be properly preserved, closely examined, creatively exhibited, and better understood by a wider audience.

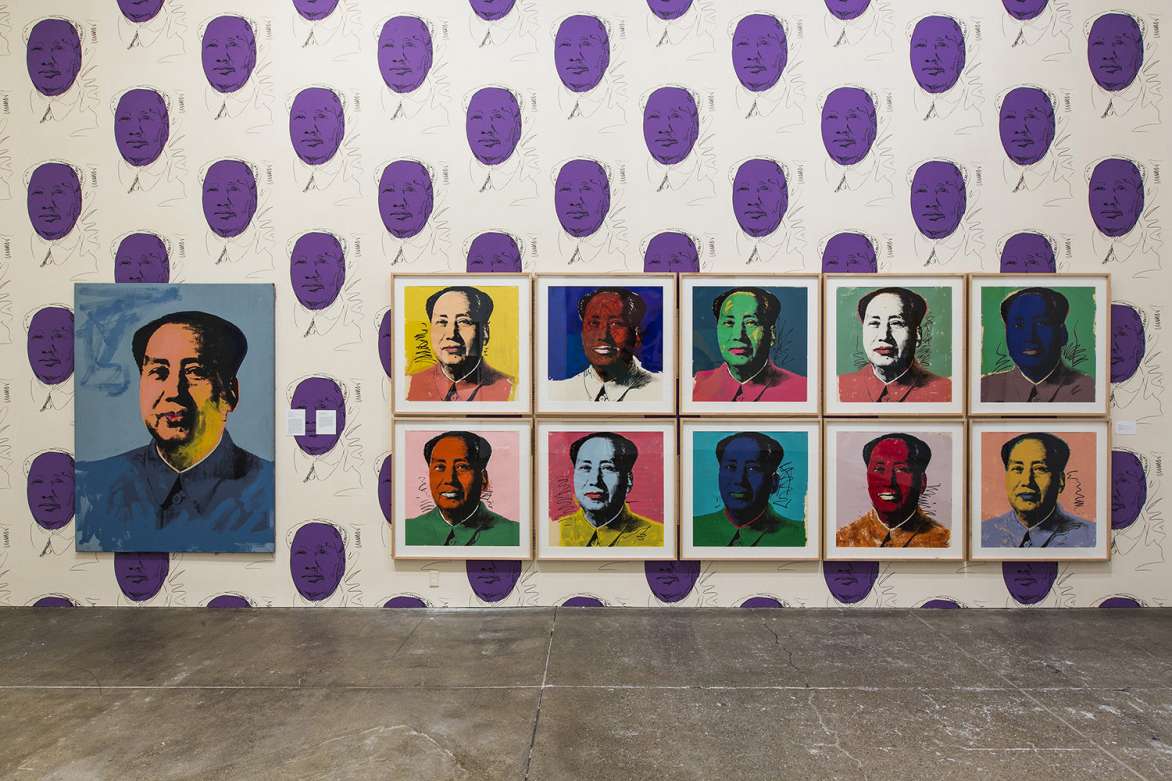

Shedding light on the full breadth of Warhol’s intense productivity, from the late 1940s through 1987, acclaimed works to lesser-known pieces that have been presented to the public for the first time. Warhol’s multi-dimensional creativity can be traced from the drawings he made while studying pictorial design at Carnegie Tech and the commercial illustrations he produced for Madison Avenue, to his groundbreaking Pop Art experiments with photographic silk-screens and innovations in portraiture, to his later collaborations with fellow artists and radical innovations in abstraction. Special galleries spotlight his extraordinary fixation on the moving image, represented by roughly 500 experimental films and more than 2,500 videos, including his TV talk shows and Factory Diaries—unedited footage of everyday life at his studio. In 1997, the Foundation transferred ownership of the rights to most of Warhol’s film and video work to the museum.

Equally significant are the museum’s holdings of Warhol’s archives and belongings. A notoriously devoted documentarian of daily life, he photographed, audio recorded, and videotaped thousands of social interactions and fleeting moments, both personal and professional. He was also an obsessive collector, saving periodicals, press clippings, posters, photos, and other ephemera. These vital historical records are preserved in the museum’s specially designed Study Center, along with 610 of Warhol’s Time Capsules (donated by the Foundation), which the artist began assembling in 1970 by tossing correspondence, receipts, bills, fan mail, exhibition announcements, phone messages, and other everyday tidbits into cartons, which he then sealed. In 2007, the Foundation provided the museum with a $625,000 grant to help fund efforts to unseal the boxes and archive the contents—a process that is still ongoing. The archives also include Warhol’s libraries, a full run of Interview magazine, and hundreds of personal items, including art supplies, 175 cookie jars, and several wigs.

Warhol would likely have approved of the museum’s encyclopedic task of preserving his belongings, and not because he thought his life was worthy of immortalizing. Rather, he was simply very fond of stuff. As he wrote in the Philosophy of Andy Warhol, “Just because people throw it out and don’t have any use for it, doesn’t mean it’s garbage.”